This article provides an overview of market research related to how national and organizational cultures relate and the importance of global competencies for global executives.

Many companies pride themselves of the culture they have created throughout their organization. It sets them apart from their competitors. They have defined their vision and their way of achieving their mission. They lay out the rules of the game. Lines of communication, accountabilities and responsibilities are clearly spelled out. Attitudes, behaviors and value systems are supposed to fit a certain framework. Employees that meet or exceed the established standards are celebrated (and promoted). The ones that fail to meet the standard will leave, be asked to leave or perhaps simply hold on to their jobs.

What is culture? Culture can be defined in many ways. Dr. Nancy J. Adler (“International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior”) states that culture is:

- Something that is shared by all or almost all members of some social group.

- Something that the older members ofthe group try to pass on to the younger members.

- Something (as in the case of morals, laws and customs) that shapes behavior, or structures one’s perception of the world.

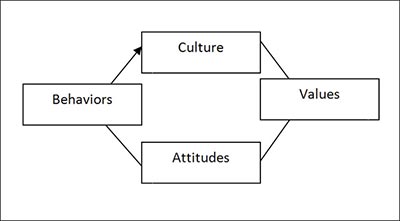

According to Dr. Adler, culture, values, attitudes and behaviors in a society influence each other. The values we have are based on our culture. Attitudes express values and get us to act or to react in a certain way toward something. Attitudes are always there when people act even if they do not see them. There is no action without attitudes. Behavior can be described to be any form of human action. The behavior of individuals and groups influence the society’s culture. There is no culture in the society without people’s behavior.

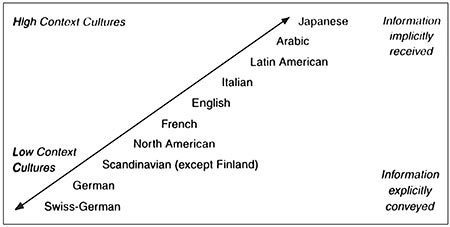

Professor Edward T. Hall’s theory of high- and low-context culture (“Beyond Culture”) explains the powerful effect culture has on communication. A key factor in his theory is context. This relates to the framework, background, and surrounding circumstances in which communication or an event takes place.

High-context cultures (e.g. Middle East, Asia, Africa, and South America) are relational, collectivist, intuitive, and contemplative. People in these cultures emphasize interpersonal relationships. Developing trust is an important first step to any business transaction. According to Hall, these cultures are collectivist, preferring group harmony and consensus to individual achievement. And people in these cultures are less governed by reason than by intuition or feelings. Words are not so important as context, which might include the speaker’s tone of voice, facial expression, gestures, posture—and even the person’s family history and status.

Low-context cultures (e.g. North America and much of Western Europe) are logical, linear, individualistic, and action-oriented. People from low-context cultures value logic, facts, and directness. Solving a problem means lining up the facts and evaluating one after another. Decisions are based on fact rather than intuition. Discussions end with actions. And communicators are expected to be straightforward, concise, and efficient in telling what action is expected. To be absolutely clear, they strive to use precise words and intend them to be taken literally. Explicit contracts conclude negotiations. This is very different from communicators in high-context cultures who depend less on language precision and legal documents. High-context business people may even distrust contracts and be offended by the lack of trust they suggest.

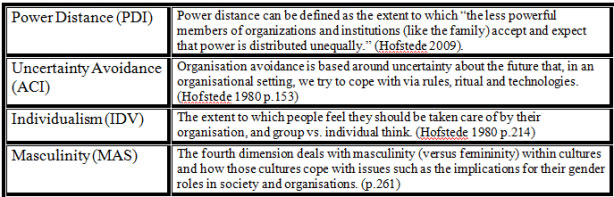

Dutch Professor Geert Hofstede conducted one of the most comprehensive studies of how values in the workplace are influenced by culture. In “Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work Related Values,” Hofstede’s research provided him with about 117,000 survey questionnaires from 66 counties. Hofstede concluded that about half the differences between countries could be described using four dimensions: power distance, individualism/collectivism, uncertainty avoidance and masculinity/femininity.

The following table is a breakdown of those cultural dimensions:

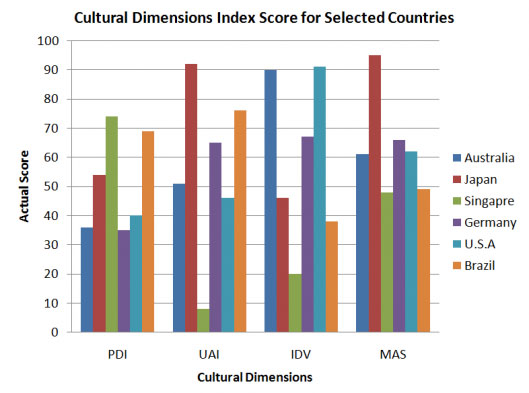

In Hofstede’s study, the cultural dimensions of each country were measured and a score was given to each country (see chart below). Hofstede’s findings reveal that measuring “success” is relative to the cultures in which one operates.

Which culture is stronger: national or organizational?

How do national and organizational cultures relate and which of them is stronger? There is no doubt that the two kinds of culture both exert powerful influences on people. It is anything but rare for employees, especially those of foreign companies, to be facing conflicts between them. A company’s culture may be informal while a country’s culture could be rather formal. A company may be encouraging and rewarding risk-taking in a country where people are generally risk-averse. Or, vice versa. All of these call for some kind of resolution to realign the company’s and its individual employees’ beliefs and behaviors.

Dr. Nancy Adler examined whether organizational culture does “erase or at least diminish national culture.” Her surprising conclusion is that there actually is more evidence to the contrary. Adler’s findings indicate cultural differences were “significantly greater among managers working within the same multinational corporation than they were among managers working for companies in their own native country. When working for multinational companies, Germans seemingly became more German, Americans more American, Swedes more Swedish, and so on.” The reasons are not well-understood but it appears that employees may be resisting a company’s corporate culture if it is counter to the beliefs of their own national culture.

Adler’s observations support the conclusion that national culture outweighs organizational culture. However, one factor may offset this: at some multinationals, a combination of targeted hiring processes and employee self-selection increasingly establishes foreign workforces that are more in harmony with the respective corporate culture. Those who fit well stay with the company, those who do not either do not get hired in the first place or leave within a few years. It’s a fine line. Potentially they run the risk becoming estranged from national cultures with possible consequences to local relationships.

In closing, some “do’s and don’ts” for companies operating in the global marketplace:

- Don’t assume that even a very powerful corporate culture will render national influences insignificant. Employees facing actual conflicts between the two are likely to respond in ways typical of their national culture, not their organizational one.

- Don’t give up on the benefit of diversity by suppressing national cultural aspects.

- Do carefully assess the organizational culture against the local cultures in all countries and regions the company is engaged in.

- Do take constructive action in order to keep employees motivated and committed when potential conflicts between organizational and national cultures arise.

- And…Do consider the cross cultural expertise of your executive search firm! Do they truly have the experience to attract and qualify global talent?